This year my wife asked what I’d like for my birthday (on my birthday). A new prime lens for my micro 4/3 camera, maybe? No, I really don’t need that. What would be a standout present – something fun? I am fascinated with how photography relates to modern art, but my education on both of these is hit and miss, and gleaned mostly from the occasional museum exhibition. I want to understand the history of photography as it relates to art, particularly modern and contemporary art theories. I went online and narrowed my desired present down to two books. I am working on the first one, but am so enthused that I’ll give you a review now!

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City has a collection of more than 25,000 works that constitute one of the most important collections of modern and contemporary photography in the world. These go back to the founding of photography, and span its history to the present.

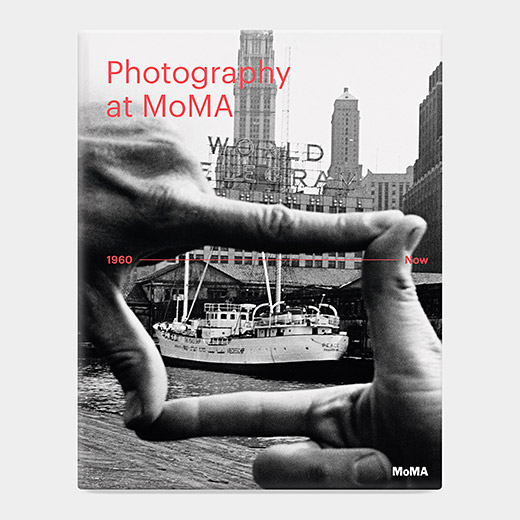

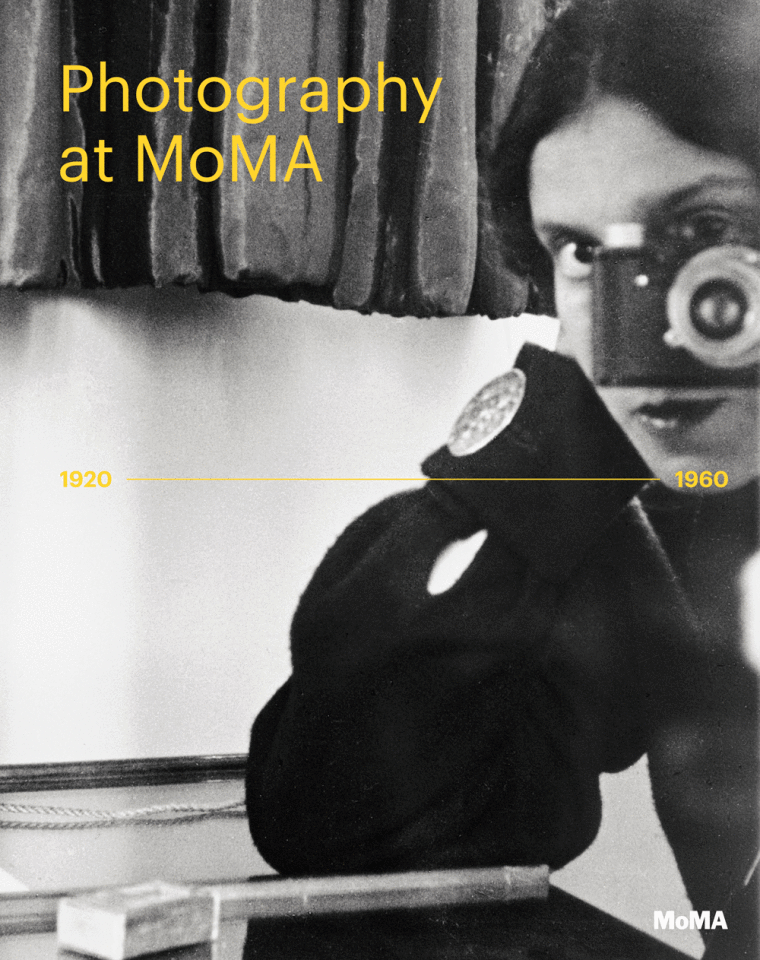

The MoMA has published two of the three volumes that will cover all of the history of photography through works from MoMA’s collection. These aren’t small books. The first is a 9.8″ x 12.3″ x 1.7″ hardback with 416 pages and 533 high quality illustrations (plates). It weighs 6.4 pounds. The other book is similar. Yet, you can find them for under $50 each.

My wife got me Photography at MoMA: 1920 to 1960, and Photography at MoMA: 1960 to Now. That is nearly 100 years of photography! The third volume covers the early years, and is still being written.

My wife got me Photography at MoMA: 1920 to 1960, and Photography at MoMA: 1960 to Now. That is nearly 100 years of photography! The third volume covers the early years, and is still being written.

Photography at MoMA: 1920 to 1960 covers the rapid development of photography during the peak of the modernist period. The book shows how the philosophy of photography grew from a purist approach to straight photography (primarily in the U.S.) to a huge variety of artistic experimentation (beginning in Europe). It covers European Modernism (Constructivism, Surrealism, the Bauhaus); the resigned cynicism of post-World War I Neue Sachlichkeit; American social documentary during the Great Depression; the beginnings in magazines of small-camera based reporting, and fashion portraits and advertising campaigns; and darkroom experimentation and personal documentary in the post-WWII period. This is exciting material, and mostly new to me.

The book begins with an in-depth introduction followed by eight chapters of full-color plates, each introduced by an essay. The thematic chapters include American Modernism, Surrealism and the Everyday, Subjective Experiments or America and the Documentary Style. It presents more than two hundred photographers, including Berenice Abbott, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Geraldo de Barros, Margaret Bourke-White, Bill Brandt, Claude Cahun, Harry Callahan, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Roy DeCarava, Robert Frank, Germaine Krull, Dorothea Lange, Gordon Parks, Man Ray, Aleksandr Rodchenko, Alfred Stieglitz, Otto Steinert, and James Van Der Zee.

Yes, this is extremely ambitious. Yes, the books are huge and beautiful. There are some negatives. The volumes are too unwieldy and luxurious to serve as an overview for a mild interest in the subject – you certainly won’t take them to the beach this summer, or pack them into your suitcase on a trip to see the MoMA. At the same time, the essays (approximately four or so pages each) are too brief and elementary for a deep dive into modern artistic theory. There is no timeline of significant events in the art world and the world at large. And the only index is an index of the plates. You really can’t easily use these books as reference books.

Yes, this is extremely ambitious. Yes, the books are huge and beautiful. There are some negatives. The volumes are too unwieldy and luxurious to serve as an overview for a mild interest in the subject – you certainly won’t take them to the beach this summer, or pack them into your suitcase on a trip to see the MoMA. At the same time, the essays (approximately four or so pages each) are too brief and elementary for a deep dive into modern artistic theory. There is no timeline of significant events in the art world and the world at large. And the only index is an index of the plates. You really can’t easily use these books as reference books.

Having said all that, I believe that these books are nearly ideal for what I am using them for. Consider me an empty vessel, or at least that’s how I am approaching this. I want to see a history of important photographs in high quality, and I want to understand the artistic context of them at the time that they were made. I want to learn about the ideas in both art and photography behind the particular photographs, and explore other works from the same period. I want to understand the rough trajectory that photography is taking. These books do most of that at 10,000 feet. I take a long time when I read these chapters, and explore the references. I’ll give you an example of how I “read” this book. I read the following in the second essay:

… “Paul Citroen’s photo montage Metropolis (Weltstadt, 1923; plate 46), a kaleidoscopic view woven out of myriad cut-out fragments of skyscrapers, unmoored from both their locations around the world and from the magazines and postcards that depicted them. Citroen’s futuristic vision of densely built urban blocks with superstructures looming over them inspired Fritz Lang in his 1927 Expressionist science fiction film of the same name.”

Of course I flipped over to Plate 46 and studied Citroen’s Metropolis montage. It really does effectively create a futuristic world, as claimed in the essay. Then I found the Lang 1927 film Metropolis on Netflix, and watched that. Then I moved on to the next paragraph. I don’t look up everything, or I’d spend weeks on a four page essay, but I do explore what interests me. A number of references in the text are to important exhibitions at the time, from which selected plates are shown. If one does an internet search on the exhibition’s name, you’ll find a link to a MoMA page, where you will find a treasure trove of photos and essays. I find that I can easily dive as deep as I want.

I am finding this book to be an excellent introduction to photography in the modernist period, and I suspect that it is unique match to what I needed. The second book,Photography at MoMA: 1960 to Now, is on the shelf in my den, where I am patiently leaving it alone until I finish this one. But here is the teaser: